Flight training in the United States before 1914 went from a do-it-yourself — build a machine and try to learn to fly it — endeavor to a growing system of flight schools across the country.

The first organized flight instruction was by the early manufacturers of aircraft, such as the Wright brothers and Glenn Curtiss.

At first, they were training members of their exhibition teams, then military customers, and then civilian customers. As interest in aviation grew and more flying machines were available, that created an opportunity for the development of flight schools in the private sector.

WRIGHT BROTHERS

The Wright brothers started providing flight instruction in France in 1909. This was done in fulfillment of a contract with a syndicate formed to build Wright Flyers in France. The flight instruction took place at Pau in the south of France. There Wilbur instructed three French students, Charles de Lambert, Paul Tissondier, and Paul Lucas-Girardville. The training program consisted of 64 flights running between five and 20 minutes each. A similar contract in Italy had Wilbur teaching two Italian officers over a course of 50 flights.

After returning to the United States the Wright brothers open a flight training facility at College Park, Maryland. As part of a contract to sell Flyers to the Army, Wilbur taught the first U.S. Army fliers. From Oct. 8 to Nov. 2, 1909, he made 35 instructional flights with three Army Signal Corps officers, Lts. Benjamin D. Foulois, Frederic E. Humphreys, and Frank P. Lahm. In 1911 the Signal Corps established its own flight school at this location.

Lahm later remarked on his training at College Park: “On Oct. 5 we moved in, built a shed for the machine, set up the pylon and track, and Wilbur began our pilot training. At the end of about three hours dual we were turned loose and made our first solo flights. A few days later I was even considered qualified to carry passengers and did so, taking Lieutenant Sweet of the Navy as my victim for a flight around the field.”

Avoiding unfavorable weather in Dayton, Ohio, in March 1910, the Wrights opened their first civilian flying school on an old cotton plantation on the outskirts of Montgomery, Alabama. The Wrights used this location to train pilots who would fly for the Wright Exhibition Co. Among the students taught here were some of the more famous Wright pilots, including Walter Brookins and Arch Hoxsey. Brookins made his first solo flight after two-and-a-half hours of instruction. He then became the Wright’s chief pilot and helped train other exhibition pilots.

Shortly after the return of Orville from Montgomery, on May 8, 1910, the Wrights opened the Wright Flying School in Dayton to continue the training of pilots who would conduct exhibition flights for the company.

After the completion of the training of the exhibition pilots, the school was opened to instruct customers of the Wright Flyers and others interested in learning to fly.

One of the advantages of training with the Wright Flying School was the use of the two-seat airplane, which was developed in 1907 for flight demonstrations in Europe. One of the Wright Flying School catalogs described their method of instruction: “Learning to Fly at the Wright School is as simple as learning to drive an automobile. All instruction machines are equipped with dual controls. The pupil takes the same seat he will always occupy and from the starting of the motor follows every movement of the instructor in getting underway, rising in the air, maneuvering, and finally landing, until these operations become instinctive. Gradually the pilot gives the actual control to the pupil while in the air until he is xapable of handling the machine under every condition of flight. Instruction and practice is then continued until the student can leave and land with perfect assurance.”

Flight training at Dayton appeared to be intensive. A story in the publication Aeronautics in 1910 reported that during the first 10 days of June students made 161 flights and were aloft for 20 hours. The Dayton flight school was in operation from 1910-1915, training 119 students.

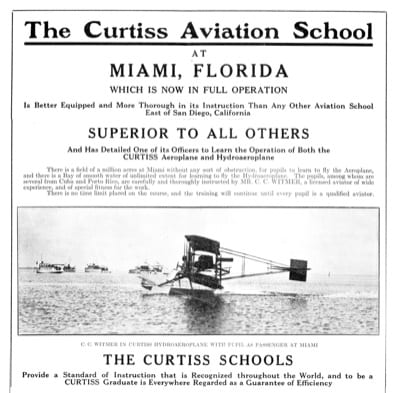

CURTISS SCHOOLS

With the Wright Co. selling aircraft to the Army, forming an exhibition team, and opening a flying school, Curtiss decided to get into the act and in 1910 formed the Curtiss Aeroplane Co. and the Curtiss Exhibtion Co.

The Curtiss Co. started instruction in two locations. The first was at Hammondsport, N.Y., where the company was located. Students at this location included Cromwell Dixon, Beckwith Havens, C.K. Hamilton, and women students, such as Blanch Stuart Scott. The second location was at San Diego on North Island where Curtiss first trained Army and Navy fliers. In order to interest the military in Curtiss aircraft, Curtiss offered to train Army and Navy fliers at no charge.

Curtiss believed every student should have a practical knowledge of aviation before attempting a flight. The student needed to know the Curtiss machine, its construction and its motor. Early on, with only single-place aircraft for training, and students on their own, instruction was cautious, starting with taxi practice up and down a field. Then short hops into the air were allowed until finally the aviator could get airborne. Only then, with considerable practice, was the student permitted to practice wide turns. Students would work toward completing the Aero Club of America pilot’s license. The initial cost was one dollar a minute for the 400-minute course ($8,600 in 2010 dollars).

Curtiss believed every student should have a practical knowledge of aviation before attempting a flight. The student needed to know the Curtiss machine, its construction and its motor. Early on, with only single-place aircraft for training, and students on their own, instruction was cautious, starting with taxi practice up and down a field. Then short hops into the air were allowed until finally the aviator could get airborne. Only then, with considerable practice, was the student permitted to practice wide turns. Students would work toward completing the Aero Club of America pilot’s license. The initial cost was one dollar a minute for the 400-minute course ($8,600 in 2010 dollars).

The Curtiss Co. was very proud of the flight school’s accomplishments, advertising in December 1911 that “More pilots’ licenses have been awarded to Curtiss pupils than to those of any other school” and that “90% of the aeroplane exhibitions throughout the United States are given by Curtiss aviators.”

PRIVATE SCHOOL GROWTH

The public performances of the Curtiss and Wright Exhibition teams, large aviation events, and record-setting flights resulted in a great increase in interest in flying.

This lead to the development of flight schools in the private sector to supplement the training done by the manufacturers.

By the end of 1911, 80 pilots received licenses, almost all of them trained at Wright or Curtiss Schools. With the addition of schools in the private sector this number would increase to 200 by the end of 1912.

The number of flyers would continue to grow at a great pace. In the winter of 1912 Aero and Hydro magazine reported that 15 aviation schools had an enrollment of 200 pupils for the winter training season, compared to the 140 enrolled during the summer season.

The schools with the larger winter classes were Curtiss, at San Diego; Lillie, at San Antonio; Martin at Los Angeles; the Moisant at Augusta, Ga.; and Thomas at Bath, N.Y. These top schools had enrollments with 20 to 30 students.

The schools with the larger winter classes were Curtiss, at San Diego; Lillie, at San Antonio; Martin at Los Angeles; the Moisant at Augusta, Ga.; and Thomas at Bath, N.Y. These top schools had enrollments with 20 to 30 students.

Some schools were still using single-seat aircraft, while others taught with dual-control aircraft. Tuition was between $200 to $500 for land machines and from $300 to $500 for water planes. It was also noted that some schools didn’t charge for breakage.

Flight training showed a successful and rapid growth. At the end of 1910 there were only 25 licensed pilots in the United States. The following two years saw the number of licensed pilots grow to more than 200. Though just coming into existence, flight training displayed signs of future potential, and at the same time succeeded in laying down the fundamentals for air training that have lasted to the present day.

TOP PHOTO: Walter Brookins, the first pilot trained by Orville Wright, with a student in 1911

So right, this “gotta have it” attitude for every wizzbang gadget that comes down the pike is just dumb. Round gauges, VOR’s, and paper charts are NOT obsolete. They ARE tried and proven and rock solid reliable.

So let’s get this straight … the Curtis school charged $8,600 in today’s dollars. The private schools mentioned charged $200 to $500 in 1910 dollars, which is about $4,900 to $12,200 in today’s dollars. That’s awfully similar to today’s cost for a Private Pilot Certificate!

This got me thinking about flight training costs over the past 100 years. From the data I found online, inflation adjusted cost of 100LL was about $4 all the way from 1970 until 2004, with a bump up to $5.50 in the early 80s. I didn’t find any data on it, but I’m going to assume flight instructors were about the same when adjusted for inflation (feel free to rip me a new one in the comments if that wasn’t true). The price of aircraft has gone waaaaay up (a 1971 Skyhawk could be had for $76,000 in today’s dollars), but many of us fly used aircraft that are far less expensive.

With all that in mind, I think the cost of flight training has only increased 5-20% over the past 40 years, when adjusted for inflation. An increase of 20% isn’t good by any means, but perhaps cost is not as obvious a cause for the decline in GA as we think.

Brett, I agree the increase in fuel cost is an issue,but it is not the downfall of G.A. My thought is that competition from other motor sports, quads almost did not exist in the 70’s and snowmobiles/jet ski’s are much more capable today. The electronic toys (including smart phones) are a major factor as well, people live in a “virtual” world and think it is the same. The huge cost of new aircraft is a problem as well because of the perception that newer is better,the aircraft publications push the newer/better in every issue and the pilot that flies without the moving mag and nexrad radar is “unsafe”. This attitude is what makes the cost so high, gadgets that can double the cost of my ’46 Champ do not make it fly. We can fly cheaply it must be promoted that it is okay to do so.