By STEVE SCHAPIRO

Truth be told, I was a little nervous. I’ve read about flying into the ice runway at Alton Bay on the south end of Lake Winnipesaukee in New Hampshire. I’ve seen videos of people who have had problems.

It sounded really cool, but the idea of landing on ice with no ability to brake was a little uncomfortable. And the landing is the easy part. Supposedly taking off is more challenging.

I fly a 1968 Piper Cherokee Arrow with the Hershey Bar wing, so you can never really be too high. If you chop the power, it glides like an old typewriter, which is to say as long as you’re over the numbers when you pull the power back to idle, you’ve got a good chance of hitting the mark. Over the years, I’ve gotten into the habit of coming in a little high and a little fast.

To land at Alton Bay, you need to fly a short field approach and execute well. That means coming in on the proper glide slope and hitting the recommended speeds. For the Arrow that’s 80 mph on base, 75 on final, over the fence at 70, and touchdown at the stall speed of 63.

Before attempting the 250-mile flight from Alexandria Field (N85) in Pittstown, N.J., I practiced my short field technique. I flew to three different airports to give myself a variety of patterns and runways to create a little more challenge. I figured if I do them all at a familiar runway, it might not translate to an unfamiliar airport.

Now the difficult part is finding a day where the weather was VFR for the entire route and with favorable winds. Alton Bay’s runway is 01-19, but they stopped using Runway 19 a few years ago. The parking ramp is at the south end of the runway, so if an airplane lands long and can’t stop, it’s heading for the parking area and where people congregate. So for safety, the New Hampshire Bureau of Aviation, which manages the runway, made the decision to restrict operations to landing and taking off on Runway 1 only.

This year the Ice Runway opened around 12:30 p.m. on Sunday, Feb. 6. By the time I saw the post on Facebook that it was open, I figured it was too late to get up there that day. So I waited and hoped there would be favorable weather in two weeks — the next time I was available.

I got lucky. Sunday, Feb. 20, the weather looked good for the entire route. The winds looked light at Alton Bay. I called the new airport manager, Jason Leavitt, on Saturday to see if he thought the runway would be open on Sunday. It had been closed for several days following warm weather and rain. He said he thought they would be open and he would be out there at 7:30 a.m. to check conditions with Paul LaRochelle, who stepped down this year after managing the runway for the past 12 years.

I arrive at the airport just after dawn and it’s cold. I preflight and call Jason. He said they will be open today, so I climb in N4858J and takeoff on the two-hour flight. As I get close, I hear several aircraft on the CTAF and enter a left downwind for Runway 1. To my left is the frozen lake, to the right is a snow-covered ridge that tops out near pattern altitude.

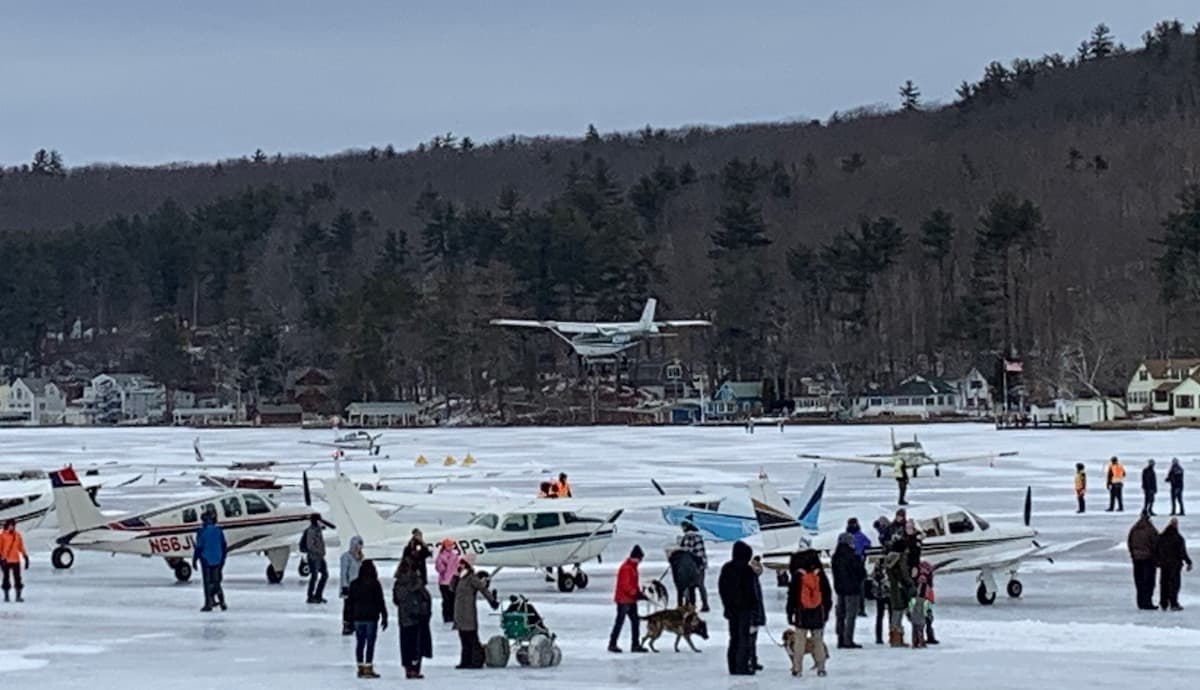

As I’m going through the landing checklist to put down the gear and add one notch of flap, I’m thinking about my short field technique. Come in low and slow. I turn left base at 80 mph, by the book. Add the second notch of flaps. The nose is trimmed up. There’s a slight crosswind from the left. Turning final and I’m a little high, but not too bad. Add the last notch of flap. The ramp, which is before the runway and slightly to the left is full of planes and there are lots of tents and people — today is Winter Carnival.

I’m lined up with the runway — or at least what looks like the runway. There is no centerline and the ice is mostly gray with some splotches of white snow from the day before. The edges are not clearly defined, at least not to my eyes. The taxiway is a little hard to differentiate as well. Fortunately, there are yellow cones marking the end of the runway and orange traffic cones marking the sides.

I’m on short final and the winds are blowing and I’m bouncing all over the place. My wings waggle and I’m wrestling with the plane. Over the radio I hear one of the volunteers say, “Gotta love a wild ride!”

Stay focused. I’m working the ailerons to counter the gusts. The plane wants to crab into the wind. My feet are dancing trying to keep the nose straight. More power to stabilize. In a crosswind, I usually like to carry a little extra power and speed to keep from blowing around. But coming into the ice runway, I’m mindful not to add too much. I bring the power back. Keep it centered, keep it coming down. Keep working it.

“Gotta love a wild ride!”

Out of the corner of my I eye I see the bandstand with the windsock pass off to my left. That means the runway threshold is 100 feet ahead. Looking good. Nose is straight, speed is good. Ease the power back. Hold her off. And touchdown.

I’m on the ice. Hold the yoke all the way back to use the elevator as an air brake, keep the flaps in, pull the throttle all the way back — even though it’s already there. Keep her rolling straight, go easy on the rudders. And don’t touch the brakes.

The airspeed indicator winds down toward 0. I just passed a sign with an arrow pointing to the taxiway. Guess I’m not making that turn off. Are there actual turn offs or can I just go between the cones? I’m slow enough now, so I gently apply right rudder to start a turn.

The nose starts to head toward the taxiway, but the plane is still heading down the runway. Oh, crap. Keep it under control. The speed bleeds off as the turn continues, I’m not sliding anymore and I’m clear of the runway. I guess that’s what it’s like to do a coordinated, slow skid. I add some power to complete the turn and head down the taxiway.

The volunteer marshalers wave me into parking and another marshaler points to an empty spot on the west side of the ramp between a Cherokee and Cessna.

I’m able to spin around and shut down. Two volunteers attempt to push me back. Surprisingly my plane is not sliding well. A third volunteer lends a hand as I try to steer a bit with the nosewheel and then I’m parked.

I open the door, and to my surprise I’m greeted by Paul LaRochelle, who I recognize from Facebook. He welcomes me to Alton Bay and hands me an ice chip — a poker chip that has a picture of a Cherokee and 2022 on one side and “I landed on the ice runway B18 Alton Bay, New Hampshire” on the other.

Welcome to Alton Bay, the only FAA certified ice runway in the lower 48 states.

Of course, landing is only half the fun. Taking off is supposed to be more difficult.

When it was time to leave, I notified a volunteer, did my preflight walk around, and climbed in. There were a few onlookers behind the plane, so I let them know I was getting ready to start and asked them to move off to the side for safety.

I was a little surprised that when the engine came to life the plane stayed where she was. That was a relief. After slowly going through my cockpit checklist to give the oil some time to warm, I signaled the volunteer I was ready to go. She waved me forward and with a little power I started moving. I added a little left rudder and the plane turned fairly normally. So far so good.

As I headed for the throat to the runway, there was a plane in front of me departing as well. I made sure to use as little power as necessary to move up so I wouldn’t slide. As I move up I do a mag check while rolling. I don’t want the plane to get going before I’m ready. I’m not sure how far I advanced the throttle, but it was certainly a few hundred less than the normal 2,000 rpm.

Another volunteer was standing next to the runway threshold and gave the plane in front of me an ok for takeoff. The scene from “Top Gun” where Maverick gives a thumbs up and salutes the crew on the deck flashes into my mind. I give the volunteer the thumbs up, he gives a wave. Time to launch.

I slowly advance the throttle, conscience of the possibility of the P-factor pulling the plane left. It does. I correct with right rudder.

The nose waggles left and right just a bit as I’m rolling down the ice. A little squirrely, but not bad. As the power comes up, there’s enough airflow over the rudder and keeping the plane straight is no problem. I ease the nose up and — we’re off the ice.

Climbing out requires a gentle turn a few degrees left to stay over the frozen lake and to avoid the hills. Time to head west to Claremont Municipal Airport (KCNH), about a half hour away. They’ve got the cheapest fuel around — $4.51 a gallon — and the stop doesn’t add much time to the return.

How it All Began

Over the past decade or so, flying to the Alton Bay Ice Runway has become a bucket list item for pilots, a rite of passage of sorts. When you tell a pilot you’ve been to the Ice Runway, they look at you a little different — it’s hard to tell if it’s a sign of respect or if they think you’re simply nuts. Maybe it’s a bit of both.

Pilots have been landing on Lake Winnipesaukee since the early 1940s.

“The Alton Bay Flying Club did it originally as a fly-in,” says new Airport Manager and New Hampshire Aeronautics UAS Planner Jason Leavitt. “The town of Alton does a Winter Carnival. I think they tied the two together and had the fly-in during Winter Carnival and it just became an annual event.”

Fast forward 70 years to the late 2000s. The runway was still in use, but operations were dwindling.

“At that time the airport was all but gone,” Paul recalls. “It was starting to die out. Just a few aircraft were coming in.”

Paul was a member of the Alton Business Association. They were resurrecting the Winter Carnival and were going to try to have it out on the ice. He and Steve Bell, another ABA member, wanted to have helicopter rides so they called the New Hampshire Bureau of Aeronautics.

They spoke with Aviation Planner Michael Pouliot, who asked if they were interested in taking over runway operations. They asked what that entailed. Michael said someone needed to be the manager and they could coordinate the helicopter rides. The other ABA members all looked at Paul.

“I live right here at the Bay. I look right out where we would have the ramp for the planes,” Paul says. “At that point I volunteered to be the ice runway manager. Michael Pouliot brought us the equipment, showed us the coordinates and the map for plowing the runway, and that’s where it started.”

That was in 2009 and Paul has been the Alton Bay Ice Runway Airport Manager ever since — even though he is not a pilot and doesn’t have any other aviation experience.

“He has really made the runway what it is now as far as the interest it gets and its popularity,” Jason says. “He stepped down this year, so I’m taking over for him and I’ve got some big shoes to fill.”

Fortunately, Paul promised he would teach Jason what he’s done the past 12 years to help him transition into the role.

“As far as paperwork and official stuff, I am the manager,” Jason says. “But as far as I’m concerned, he’s the assistant manager because he is out there showing me the ropes and he has a contract with the state to plow the runway.”

Setting up the Runway

The equipment to set up the runway consists of three yellow cones that are placed on each side to mark the start of the runway and orange highway cones to mark the edges. There are signs to alert people of aircraft and to keep them off the runway, taxiway, and ramp areas.

The frozen lake is a busy place in the winter. Besides the planes landing on the runway, there are ice fisherman, snowmobilers, and cross-country skiers who enjoy the ice. Before Paul took over it could be an uphill battle to keep people away from the runway.

“I changed that by getting along with them,” Paul says.

He’s helped pull shacks out on the ice and plowed areas for the ice fisherman, building a good relationship with the community — a good lesson for any airport manager.

“My motto is there is plenty of room out there for all of us to play. If you want to ice fish, if you want to cross-country ski, whatever your fun is,” Paul says. “It’s gotten to the point they look forward to the videos to know if the ice is safe to go put their shacks out. More and more people like the runway and I’ve been cooperating through the years.”

To set things up, Paul uses an Ice Runway Map the NHDOT provided that has the longitude and latitude and an aerial topography of the land and the water in the area.

“It shows an outline of what the runway looks like on water,” Paul says. “We put it in as close to proximity as it would look like on the ice. We follow the width, the length, and the coordination of where it’s supposed to be as far as longitude and latitude on the ice itself.”

The runway is 100 feet wide but the length varies from 2,300 to 2,900 feet year to year depending on the condition of the ice. The goal is to be at least 2,600 feet. This year the runway was just over 2,700 feet, according to Paul.

Runway 1 begins about 100 feet north of a bandstand on the left. That’s where you’ll find the windsock — orange means the airport is open, a white windsock means the airport is closed.

The taxiway is 50 feet wide and connects to an area called the throat between the runway and the parking area. There is room for about 30 aircraft if you park with wings overlapping or 20 aircraft parked wingtip to wingtip.

The season for Paul and Jason begins in late December. Once there is about four inches of ice, they begin checking conditions and planning. There is no guarantee the runway will open. The ice needs to be at least 12 inches thick. Since Paul has been the manager, there were three years when the runway didn’t open – 2011, 2016, and 2020 – because the ice was too thin or uneven.

Paul began keeping a journal in 2010, noting the runway conditions each day, to go along with his daily posts on the Alton Bay Seaplane Base and Ice Runway Facebook Page. The earliest the runway has opened was Jan. 8 in 2010. The latest was Feb. 10 in 2021.

Once the runway is open, there’s no guarantee how long it will stay open. The status can change day to day or even hour to hour. The best year was 2014 when it was open from Jan. 19 through March 29. The latest the runway is allowed to be open is March 31. In a good year, the runway might be open for as many as six weeks, but most years it’s only open for about three weeks beginning in late January and closing in late February.

This year the runway opened on Feb. 6 and officially closed on Feb. 24, although Feb. 21 was the last day conditions were good enough for aircraft to come in. So while the runway was “open” for 18 days, there were only seven or eight days that the runway was usable and aircraft were allowed to land.

If It’s Open, They Will Come

Given the few days the runway is actually open for operations, getting to Alton Bay becomes even more special, particularly for pilots who aren’t local. In years past, the farthest someone would fly was New Jersey or eastern Pennsylvania — about a two- or three-hour flight depending on the aircraft. But as the runway has grown in popularity through Paul’s Facebook posts and increasing press attention, pilots have journeyed a little farther.

Jon Eisman flew all the way from Miami to Alton Bay in his Cessna 182 this year – a trip of more than 1,200 miles one way. He logged 9.1 hours of flight time from Tamiami, Florida, (KTMB) to Norwood, Massachusetts, (KOWD) with two stops for fuel. The next day he completed the last 75 miles in less than an hour of flying. And he wasn’t even sure he would land.

“What I had planned to do psychologically was fly from Norwood to Alton Bay and not land. I was only going to do a low pass or two and check it out and be completely satisfied.”

As Jon approached, the winds were gusting 8 to 10 knots and it was a little bouncy. He overflew the field and made an approach. He was a little fast so he went around. Another plane landed. He made a second approach. His speed was better, but he went around again. The third time around he got his airspeed down to 65 knots, did a real low pass, and touched the mains.

“I was still too fast, I would have over-rolled,” Jon says. “That was all good. I said OK, that’s it for Alton Bay this year. At least I got to see it and I got to talk to Jason on the radio.”

He decided to go around one more time. On this approach he set up a longer final and “that was the secret sauce.” He came in low, full flaps, and was down to 59 knots. He landed and as he was rolling out, the plane wasn’t slowing down. Jon didn’t use any brakes and there was a little tailwind. He thought about going around but even on pavement the 182 has a lot of torque and you have to bring the throttle in slowly or it’s going off the runway. On ice that could be a real problem.

He was down to 10 knots, the end of the runway was getting close, and then the plane weather vaned perfectly, 170° to 180°. He gave it a little touch of power and he was taxiing back.

“Holy s#*t! I did it. I felt like I landed on the moon,” Jon says. “It was so slippery. And that was it. It was like an Indiana Jones moment — this is actually for real.”

Even though it was a weekday when the airport usually is not staffed, Jason was there to give Jon a poker chip and certificate.

“I didn’t expect any of that and we got to meet. I watch him on Facebook every morning while making coffee at 5:30 a.m.”

On weekends, the runway is staffed by about six to 10 volunteers to help direct traffic and park aircraft. One of the volunteers has a clicker to count how many come in. The day I was there, 115 planes landed. That was about half of the approximately 250 aircraft that came in this year.

Since Paul has been keeping track, the most aircraft in one year is 732 in 2010.

“Some of the really nice weekends when conditions are really favorable, the Ice Runway has more operations than Manchester Airport,” Jason says. “At times it is the busiest airport in New Hampshire.”

All types of aircraft come in. Besides the usual Cherokees and Cessna 150s, 172s, and 182s, there were skiplanes and seaplanes, as well as an amphibious Super Petrel LSA on the day I was there. Among the many taildraggers were a Luscombe that flew three hours from Aeroflex-Andover (12N), a Husky, a Decathlon, and a Globe Swift. There was even a twin-engine Cessna Skymaster that came in. It’s not the first twin to land at Alton Bay. In past years a Beech Baron has come in.

Steven Lucia flew his Bonanza A-36 in for the sixth time in 2022. He keeps coming back because “it’s just a fun day,” he said. “It’s fun watching people come and go.”

He added this was the second time the runway was very slick.

“On the rollout it was getting a little squirrely,” Steven said. “Most of the time it has a brine on it and it’s very uneventful.”

The most surprising aircraft that has ever landed was a glider. The pilot called ahead to coordinate with Paul. They came in on a weekday and Paul closed the airport so they could land. The pilot brought along his own towplane, a Piper Pawnee, so he could takeoff — but not before giving Paul and another volunteer rides.

Preparation is Key to Flying in

If you plan to fly into Alton Bay next year, it is important to prepare well ahead of time. To start, watch the FAA WINGS seminar to familiarize yourself with the layout, procedures, and alternate airports in the vicinity in case you aren’t able to land.

Without the ability to brake, Jason recommends practicing short field takeoffs and landings.

“You want to come in at the appropriate speed and land where you want to land. You don’t want to float too long or get too far down the runway,” Jason says. “You can’t just apply brakes to stop yourself. You have to roll to a stop.”

Jason or Paul post on the Alton Bay Seaplane Base and Ice Runway Facebook Page at least daily to provide condition reports and whether the runway is open or not. There is a phone number (603-271-7398) that gets updated with current conditions, and of course, checking NOTAMs is a must before flying in.

On departure, run-ups have to be done while taxiing, similar to what is necessary in a seaplane.

“You’ve got to get yourself lined up with the runway and do your run-up while rolling,” Jason says. “You can’t stop and hold yourself still.”

Taking off can be tricky because nosewheel steering is less effective on the ice and there is little to no braking ability. A good crosswind can push you around a bit. As you advance the throttle, it needs to be done slowly and smoothly to build enough airspeed to provide rudder authority to counter the P-factor. With less directional control on a slippery surface, the plane can easily veer to the left if you advance the throttle too quickly.

Paul always recommends that a pilot flying in for the first time come in with someone who has been there before and land once with them before trying it themselves.

“You really have to be pretty proficient in your flying abilities — both landing and taking off,” Jason adds.

A few other things to remember: Alton Bay has no facilities or fuel. The “FBO” this year was a red ice fishing hut where there was a sign-in book, and Jason’s wife Janet who was filling out certificates to record your achievement and offering hot chocolate or coffee to pilots. She also had hats and buttons for sale.

It is recommended that you bring chocks, an engine cover/blanket, and any tools that you think you may need. Cleats or clip-ons for your boots are also really helpful to give you better traction and, of course, wear warm clothes and shoes in case you’re on the ice longer than expected.

Another consideration is the possibility that you might get stuck there. If conditions deteriorate after you land, be prepared to stay overnight. For instance, if the sun starts melting the snow or ice, or the winds shift to favor Runway 19, the runway may shut down.

Jason also recommends bringing tie-down stakes, either the corkscrew type or something like the Claw. It’s unlikely you’ll get stuck overnight, but it’s always best to be prepared.

Why should someone fly to Alton Bay?

“For the experience and the excitement of landing on the ice,” Paul says. “It’s just the uniqueness of it, and the warm charm of the town, going to any of the local restaurants that are right here in the Bay in walking distance. It’s well worth it for anyone if they get a chance to experience it.”

“It’s certainly not something that a lot of pilots do,” Jason said. “It’s good bragging rights and it’s definitely a good proficiency test.”

End of an Era

With Alton Bay shutting down for the season, is it the end of an era?

“I think it’s time for someone else to come in,” Paul says. “I’ve done it for 12 years. I’d like to be able to relax, spend a little more time with my family.”

It’s very time consuming to be the only Ice Runway Manager in the lower 48 states. Besides leading a team of volunteers who plow the runway and put out and pick up the equipment, Paul was out in the cold every day for three months each winter, for 12 years. He was constantly checking and maintaining the ice, changing the NOTAMs on an open and closed basis, and posting Facebook videos every day.

“What nobody else sees is the answering machine that I have at home. I change it daily,” Paul says. “It just got to be too much for one person, doing that part of it.”

So this year, Paul LaRochelle taught Jason Leavitt everything he’s learned. When Jason volunteered to take over, Paul said, “I’ll help you this whole season to get it going and to make sure you understand exactly what I’ve done each of the past 12 seasons.”

Jason came out with Paul each and every time he checked the runway. Paul would do a video and then Jason would do one. And they did some together. The two hit it off right away.

“He’s doing great,” Paul reports. “I love what he’s brought to the table.”

Jason is more technical and computer savvy – posting NOTAMs from his phone, where Paul would do so from his computer at home. Paul is more of a hands-on type of a guy, enjoying being out with the plow and the people.

At the end of the season, the Bureau of Aeronautics asked Paul if he would like to stay on — not as manager, but as the assistant manager maintaining the ice on the runway.

“I thought about it, I talked to my wife about it … I said yes.”

In 2023, you can expect to see both Jason and Paul working together to keep the Ice Runway open for everyone to enjoy.

“I’m back in,” Paul says. “Now we’re the dynamic duo.”

Absolutely an awesome experience with thanks to the support of Jason and Paul. Thank you Steve and GAN for adding me to the story. My Round trip to B18 was nearly 3,000 Miles and 21 hours. Would it again? 2023 can’t come too soon !! The preparation for this trip was nearly as good as the ice landing. Practice, personal minimums and proper ADM made of fairly stress free.