There’s a heavy-duty logic that a former maker of boilers and radiators in the pre-aviation age would go on to build an armored patrol aircraft for Germany in World War I.

Hugo Junkers and his team created the metal-skinned J.I (with a Roman numeral I) that was also, confusingly, known as the J4 at the company.

Hugo Junkers was an early advocate of metal airframes and his use of steel — and later corrugated aluminum — for skin surfaces during World War I set a design rationale that survived into the 1930s.

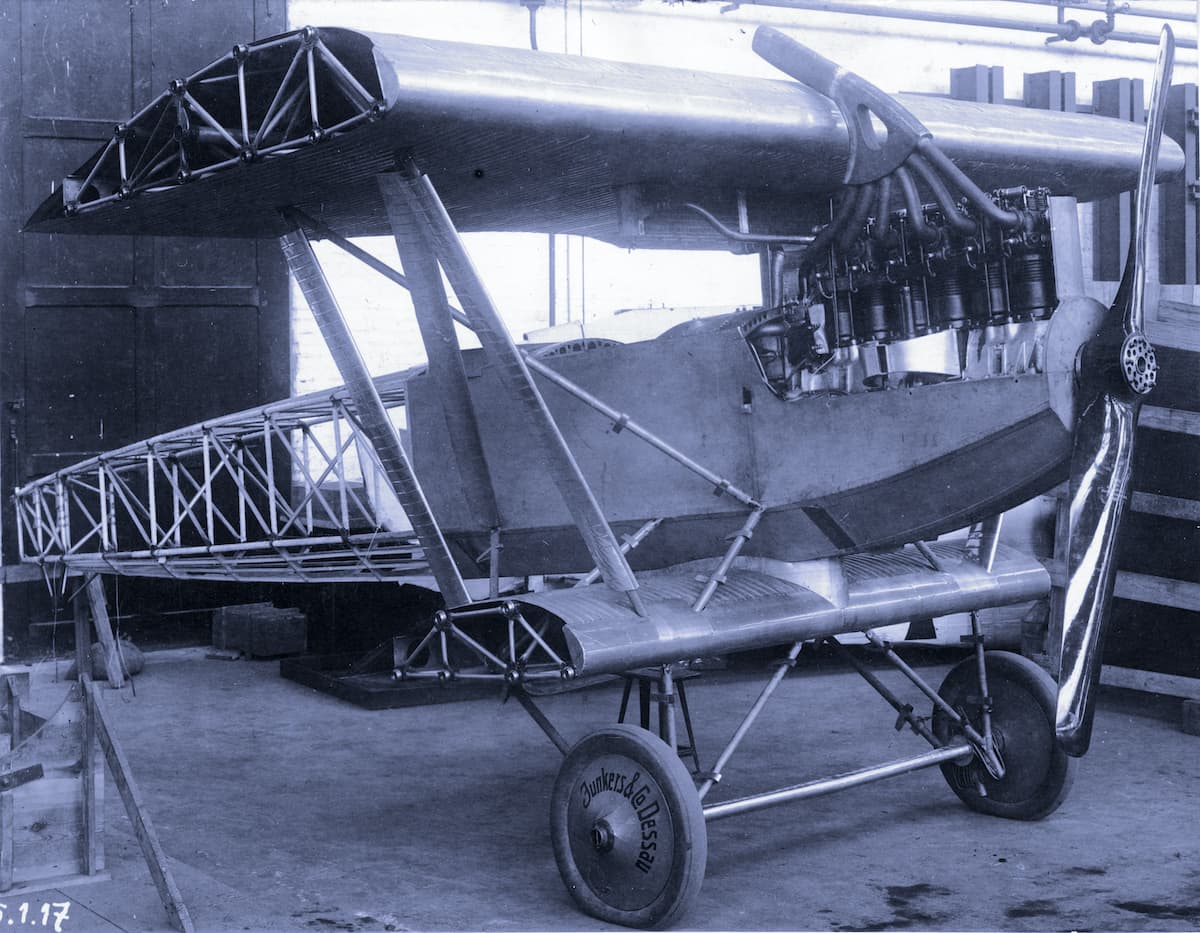

Germany asked Junkers to design an armored two-seat aircraft for close-support missions, where small-arms ground fire could be particularly hazardous. For the J.I, rolled out in 1917, Junkers employed smooth chrome-nickel sheet steel 5 millimeters thick — about 3/16 inch — to create an armored capsule that protected the engine and crew from ground fire. Everything from behind the propeller hub to the rear seat was encased in armor.

From a steel bulkhead behind the gunner-observer, a tube frame formed the aft fuselage. As designed, the aft fuselage was fabric covered. Late-production J.Is used corrugated skin to wrap this section.

The top and bottom wings of the sesquiplane J.I were supported by struts emanating from the fuselage and between the wings near the body, but otherwise they were essentially cantilever designs that rode above and slightly below the fuselage. A keel on the bottom of the fuselage provided additional contact for the lower wing.

The wings were sheathed in corrugated aluminum skin that concealed a series of aluminum tube upper and lower spars with riveted diagonal bracing providing a sturdy truss.

Power for the Junkers J.I was supplied by a 200-horsepower Benz Bz IV six-cylinder inline water-cooled engine. Hinged steel armor panels protected the engine that rode slightly above the fuselage to provide the desired thrust line for the propeller.

Early J.Is used an exhaust manifold that arced over the top wing. Later aircraft in the series used a straight vertical exhaust manifold.

In an era when wood, wire, and fabric were the norm for airframes, the metal J.I was a standout. It has been said the only wooden airframe part on this Junkers was the tailskid, crafted from ash. Metal main landing gear struts supported a cross axle that used elastic shock cord to tame landing impact.

Metal cranks and pushrods linked the controls to the cockpit. The Junkers team believed this would be more combat-survivable than traditional control wires.

The Junkers J.I spanned 52.5 feet. Length was just over 29 feet, 10 inches.

The Junkers J.I weighed in empty at 3,885 pounds, just 115 pounds shy of two tons. Loaded, the aircraft relied on its Benz engine to propel more than 4,785 pounds.

That engine could tease about 96 miles per hour out of the J.I at best. It took more than a half hour to reach 6,560 feet, although that may have been of less use in its career as a patrol and resupply aircraft for the German army.

The pilot had two fixed forward-firing Spandau machine guns at his disposal, and the rear cockpit had one flexible-mount Parabellum machine gun for defense. An attempt at placing two fixed machine guns firing toward the ground proved ineffective due to aiming and speed issues.

The armored Junkers reached frontline units toward the end of 1917. With an understandable learning curve — and the need to find acceptance from its crews — the radical J.I gained affection for the rugged protection it offered. Assigned the task of determining the ebb and flow in the front lines of combat, crews in J.Is flew at low altitude.

The back seater sometimes had access to a radio he could use to communicate to a command post at the rear of the fighting. At other times he used message bags airdropped where needed.

German infantry used cloth on the ground or burning signals to indicate their positions to the J.I crew.

As the war dragged on in to 1918, in instances where isolated German infantry pockets could not be resupplied by ground, the durable Junkers J.Is airdropped supplies and ammunition to them.

Of 227 J.1s built, only one basic airframe survives, in rugged shape, in the Canada Aviation and Space Museum in Ottawa. It was a war trophy sent to Canada in 1919.

A restored fuselage of another example is in the Italian Air Force Museum.

Wonderful story / photographs / details on this aircraft design. Thanks!!