By KEVIN BROOKER

Starting an impassioned conversation among a group of pilots isn’t too difficult. Just ask about a known controversial topic, toss it out into a group of pilots standing around, then just sit down and listen.

In case you are at a loss, here are a few starters: Lean of peak vs rich of peak, side slip vs forward slip, the value of compression checks, and at what temperature to pre-heat.

And don’t forget one of my favorites: What is the best knot to tie down your aircraft?

Asking about knots is an especially good topic to bring up when someone is actively tying down an airplane. However, I don’t engage in any of these shenanigans when an instructor is with a student.

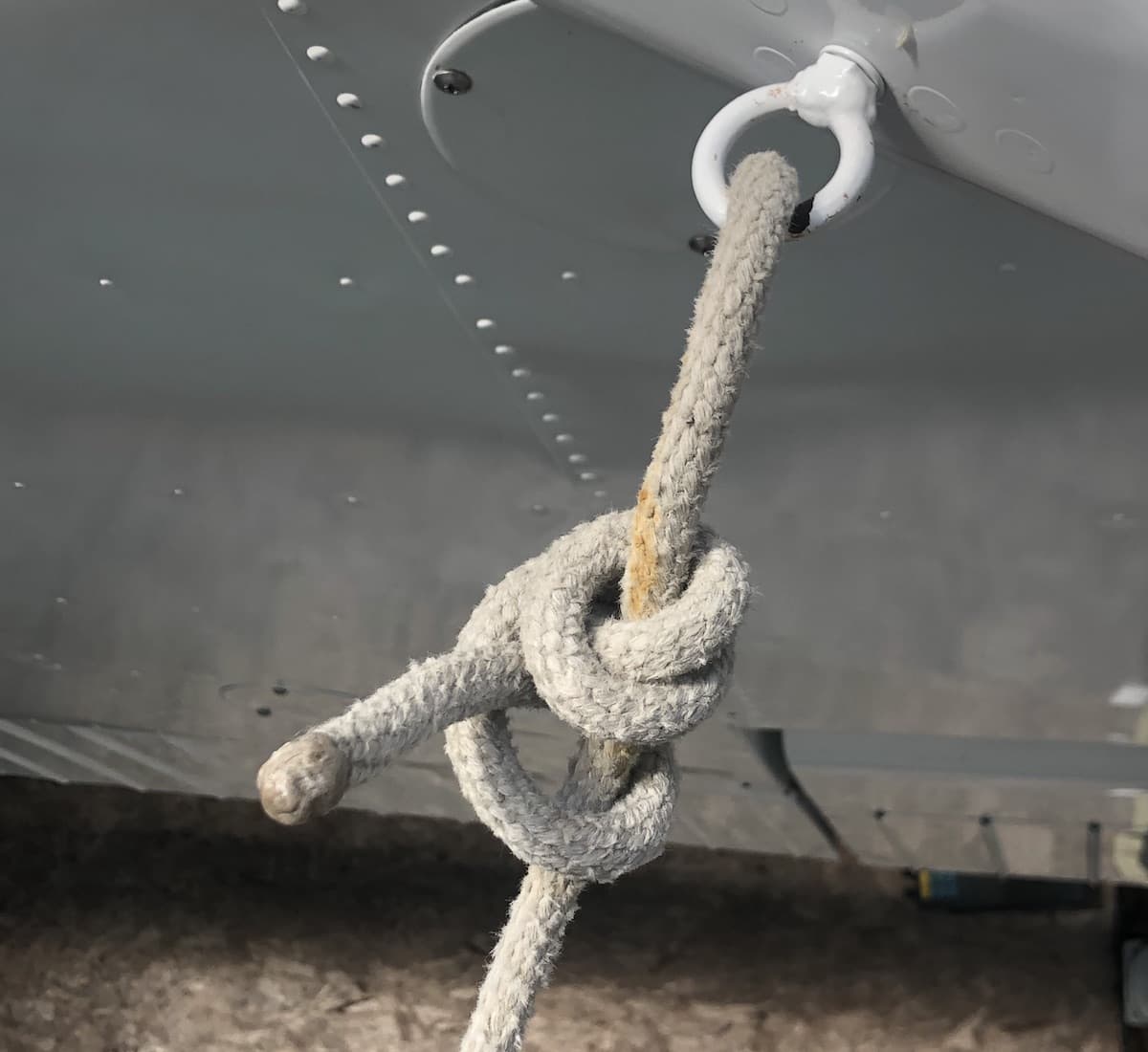

My flying career began at age 11 when my neighbor took me for a ride in his Cessna Skylane. After the flight John showed me how to properly tie down the airplane using a Midshipman Hitch, the most common knot used by pilots.

Part of John’s instruction — and what has really stuck with me — is to tie the knot close to the ring. Even if it’s tied incorrectly, the limited slippage will keep the aircraft more secure than a lot of slack in the line. It made sense in 1978 and still does in 2025.

In his book, “A Few Good Knots,” Forbes Pedigrew states the qualities of a good knot: “There are five boxes that a good working knot should tick. The first four are: It should be secure, quickly made, easily checked, and yet readily undone. The fifth box is no less important — it should be matched to its use.”

A quick survey of tie-down methods used at airports were knots of various types tied in rope; ropes with some permanent fixing device such as a carabiner or hook; webbing straps (ratchet or cam lock) with hooks on either end; and some combination of the those.

For this discussion, I decided to focus on knots in ropes.

The most common knot used by pilots is the Midshipman’s Hitch, also known as the Rolling Hitch, Magnus Hitch, Taut-line Hitch, Tent-line Hitch, Rigger’s Hitch, and Adjustable Hitch. It is believed the knot gained popularity with pilots because it was used to secure fighters to the decks of aircraft carriers during World War II.

The knot is relatively secure but can slip, especially when improperly tied or subjected to repeated cycles of loading and unloading. This knot reduces the breaking strength of a rope by 35%.

A small percentage of the airplanes at my home airport are tied down with a Bowline. This knot is well known for holding fast, untying easily after loading, and being a bit difficult to tie. Another benefit is how little the bowline reduces the strength of the rope when tied — just 20%.

Start at the Beginning

We can’t tie knots without ropes and these are often overlooked when selecting a tie-down method.

The material that makes up a rope is important in how well your aircraft will be secured.

Exposure to sunlight, chemicals (gasoline, jet fuel, engine oil, washing and de-icing fluids, agricultural chemicals), grit, and being driven over all degrade the strength and knotability of a rope.

Most ropes used for aircraft tie-downs are synthetic, made up from some sort of poly-plastic. How well these resist the effects of the chemicals and dirt vary.

The most common families of rope found at airports are laid or twisted rope, hollow braid, and braided with a solid core.

Laid or twisted rope is made up of finer threads twisted together into yarns, then twisted into larger strands before three strands are twisted or laid together into the final rope.

Hollow braid has the yarns or fibers braided into a hollow sleeve. Braided ropes with a solid core have an outer sheath similarly made to the hollow braided ropes, which surrounds some type of core held inside. These ropes tend to be the strongest and most abrasion resistant.

Time to Test

In order to compare various knots in a variety of ropes, I constructed a test rig. The set-up used a crane scale hanging from the lifting arm of a hydraulic engine hoist. A ring made from 1/4-inch steel represented the tie-down point similar to what’s found on many GA aircraft. The bottom end of the rope was wrapped around a length of three-inch PVC pipe five times, allowing the friction to take the load and eliminate another rope-weakening knot.

For the sake of consistency — with one exception — each of the tie-down knots was made approximately three inches from the tie-down ring. Each rope and knot combination was pulled until the knot slipped, held, or the rope broke. At 350 pounds of tension the pull was stopped.

Each rope was tied in four ways: A Midshipman’s Hitch while about 20 pounds of tension was applied to the rope; a Midshipman’s Hitch with a loose rope before sliding the knot, creating as close to 20 pounds as possible; a Bowline; and two Half-Hitches up close to the ring.

Two Half-Hitches tied close to the ring were included since I have been known to claim “even two half-hitches up tight will work…” Time to put my pride where my mouth is.

Here is what I discovered from my tests:

I started with a 7-mm solid core static rope, which is meant for use while climbing as a cordolette for rigging anchors and hauling loads. Tied with a tight Midshipman’s Hitch (TMH), it held 250 pounds before slipping and was very easy to untie. When tied as a loose Midshipman’s Hitch (LMH) the rope slipped through the ring with only 45 pounds of tension and was also very easy to untie. Two Half-Hitches (2HH) slipped three inches before holding to the 350 pound limit and required pliers and a few minutes to untie.

Next I tested a 6-mm solid core, another climbing rope rated to 1,843 pounds tensile strength. This is in my personal tie-down kit. It slipped at 320 pounds with the TMH and 163 when using the LMH. The 2HH knot slipped for two inches before holding to 350 pounds and requiring pliers to untie.

Third was a 5-mm Kevlar core climbing cord with a breaking strength of 2,000 pounds. This stuff doesn’t stretch, is stiff, and difficult to knot, similar to tying wire. Unless you tie a Bowline, this rope is not very good for securing airplanes. It slipped at 95 pounds TMH and 55 pounds with the LMH. With 2HH it did hold to 300 pounds with three inches of slippage and was difficult to untie but no tool was required.

The fourth test involved a 1/4-inch hollow braid polypropylene. This rope was terrible. The TMH slipped at 51 pounds and 25 using the LMH method. The Bowline held to 350 with a bit of slipping as the knot tightened. This rope was the only time a Bowline required a tool to untie and the fibers appeared to have melted from the friction of tightening. The 2HH held after a three-inch slip and could only be released by cutting the rope free with a knife.

Then came a 3/8-inch hollow braid polypropylene. The 1/8 inch extra diameter made a huge difference in the hold strength of the knots. The TMH held 200 pounds and was pretty useless after it slipped. The LMH slipped to uselessness at 97 pounds. The Bowline held the 350 pounds and was difficult to untie, but did not require a tool. The 2HH held to 350 after slipping almost 5 inches of rope and the pliers were needed to untie the rope.

Next was a 10-mm dynamic climbing rope. This is a stranded core kernmantle (straight yarns along the length of the non-braided core) style rope. These ropes are meant to stretch to absorb the energy of a falling climber. This rope was retired from climbing 17 years ago. It has been outside on grass in the sunlight.

The TMH held 245 pounds and was super easy to untie. The LMH slid at 50 pounds. The Bowline held 350 pounds and was easy to untie. 2HH slipped almost 12 inches before it grabbed and ultimately slipped at 167 pounds. With each knot this rope was very untie friendly.

Then I tested a 9/16-inch static tree climbing rope, which has a braided solid core with a braided outer sheath. This rope is static and built to limit the stretch when pulling or lowering sections of a tree.

The handling of this rope was great and was overall the easiest to both tie and untie all of the knots. This knot held 256 pounds with the TMH and 177 with the LMH. Again, the Bowline held the full 350 pounds. The 2HH slipped two inches before holding 350 pounds and was difficult to untie with no tools needed.

Next, I found a 5/8-inch, three-strand rope lying in the grass at a tie-down. I have no idea of its age. This rope felt typical of what is left on the ramp. It was stiff and gritty and almost as difficult as the kevlar cord to tie.

The knots were ugly and looked horrible, but held surprisingly well. The TMH held the 350 pounds and was very easy to untie. Both the LMH and 2HH slipped at 300 pounds. And there was no trouble untying either of them. As expected, the Bowline held and untied with little effort.

I then found a 3/8-inch ratty faded and fuzzy hollow braid on an asphalt ramp. It was included as, unfortunately, ropes like this are very common on many public use tie-down areas. The expectation was the worn and abused rope would fail under load. Those expectations were wrong. The TMH, LMH, and 2HH held 300 pounds and were easy to untie and the Bowline performed as expected.

The King of Knots

By far the best performing tie-down knot is the Bowline. It never slipped and was easy to untie with the exception of the 5-mm cord. This knot had minimal slippage as the knot tightened. The Bowline is known as the “King of Knots,” a well-deserved title.

The Midshipman’s Hitch worked better than I thought it would. Tied correctly, while under some tension, it holds almost as well as a Bowline.

The one knock on the Midshipman’s Hitch is it is subject to slipping if handled or bumped while under tension. Pushing up on the knot inevitably caused slippage.

The practice of pulling out the slack after tying the knot proved to be a poor performing knot. It failed at about 50% of the pull of a tension-tied Midshipman’s Hitch.

Two Half-Hitches might work, but not very well. It does hold after it tightens up, but is miserable to untie. My pride has taken a hit on this one and apologies to anyone subject to my diatribes on the praises of using the two Half-Hitches as a proper tie-down knot.

Oh, and in case you were wondering: Without a mixture control on my Taylorcraft I have no dog in the Lean of Peak vs Rich of Peak argument; there is no functional difference between a forward and a side slip; certain aspects of compression checks are worth knowing; and always preheat below 35° F.

And I have become a big fan of the Bowline tied up tight to the ring.

This is how I was taught to tie down airplanes many years ago. Very simple to do, works well, and super easy to unite. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fiQ4emNz4gY.

Ohh. I know!! I know!! Pick me 😎. LOL. Good challenge. Right up there with “what color should I paint my airplane?”

In teaching the A&P syllabus we taught both bowline and taut line hitch with the latter being the faa preference. As a CFI I teach the same HOWEVER, the taut line hitch is intended, and works much better, on a taut line. If you tie it on a slack line it’s already at a loss. Two taut line hitches, one a few inches below the first, or a simple half hitch below the taut line hitch make an almost ideal mooring.

I’ve been tying bowlines since my first sailboat at 10. They are excellent knots but knot easy to tie in tension or under a low wing. I will almost always use one for tying the line to the ground anchor but then use a TLH at the airplane end. WHEN you use a bowline try tucking a bend by the bitter end so you have a tail that, when pulled, slips the first part of the knot to untie it.

As for chains,….NEVER in tension with a fixed anchor. Even on a cable run leave some give. I had a williwaw (typically up to 90 kt blast as a pressure ridge crests a mountain range) come through Kodiak and the chain on cable still jerked the tie down ring right out of one spar on my C195. Fortunately some good CG aircrew had taken shelter in a nearby hangar doorway and ventured out to get a strap across the main ldg gear before the airplane danced itself into scrap. The aircraft IS going to dance on it’s shock absorbing landing gear. You won’t stop that. You do need a tie down that absorbs it without jerking the airframe…

Gotta run. I’m supposed yo be finishing my part of Lisa’s Citabria panel… but this was more fun…

My advanced rating flight instructor taught me to never use the chains with hooks at tiedowns, and I passed this advice on to my students. There are several reasons for this.

. For instance, in very gusty wind situations the plane can start rocking such that the chain goes a bit slack, then gets jerked tight. This is like water hammer in a pipe. The hard impacts can bit by bit deform the hook until it bends enough to pull through the tiedown ring.

. OR – the hammering on the tiedown point on the aircraft can cause it to fail or deform the aircraft structure.

. I learned to use a strong tiedown rope and carabiners on each tiedown point. If I could not attach a caribiner to the tiedown point on the ground anchor then I would attach it to the chain close to the ground.

. The big advantage of using ropes is that the length of rope permits a nice amount of give, preventing strong jerking forces from being applied to the tiedown points on the aircraft or the ground anchors.

. Another thing to consider: don’t use open hooks anywhere in your tiedown system. If used on the wing tiedowns then gusts can cause them to bounce right out of the tiedown ring.

. And another advantage of carabiners is that if you end up in a big hurry, like in rain, they are fast to attach and fast to disconnect. If needed you can disconnect and throw the rope mess into the plane and sort it all out later.

For regularly used airplanes, maybe ok; but if left for multiple years untied, the Bowline is a female dog to untie — FAR worse than double half-hitches (and double half hitches have a strong tendency to self untie if tension is lost on them — as in passing wind gusts. I would never use them except on boats with wet lines). I have found Tautlines to hold well, even for multiple years and withstanding gusty weather, and easy to release when needed — even after multiple years undisturbed (as on my radio antenna guys).

I preach using the bowline knot, for all the above reasons, but it is very difficult to tie with no slack in the line. So I place the plane as close as possible over the wing tiedowns, and use a bowline at both ends. Then roll the plane backwards to tension the ropes and tie down the tail.

Bowline rules. Old Eagle Scout here. “The rabbit comes out of the hole, around the tree, back down the hole.” Yee haw.

Good things to know, Thanks for the all the work testing the ropes and knots.

I’ll practice the Bowline knot, although most of the airports that I visit in No. CA use chains.